It’s finally out—The big review paper on the lack of political diversity in social psychology

This piece is available in audio format on our podcast, “Heterodox Out Loud: the best of the HxA blog.” Narration begins at 1:50.

Heterodox Academy has its origins in a collaborative effort by five social psychologists (Jose Duarte, Jarret Crawford, Lee Jussim, Phil Tetlock and me) and a sociologist (Charlotta Stern) to study a problem that has long been noted in psychology: nearly everyone in the field is on the left, politically. We have been working together since 2011 to write a paper explaining how this situation came about, how it reduces the quality of science published in social psychology, and what can be done to improve the science. (Note that none of us self-identifies as conservative.) In the process we discovered the work of the other scholars in other fields who joined with us to create this site.

Our paper is finally published this week! A preprint of the manuscript was posted last year, but now we have the final typeset version, plus the 33 commentaries. Here is a link to the PDF of the final manuscript, on the website of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. (Thanks to Paul Bloom for his wise and patient editorship.) But because our article is long (13 dense pages) and the 33 commentaries are longer (another 31 pages) — and then there’s our response (another 7 pages) — we recognize that few people will ever read the whole package.

For all these reasons, we offer here a “CliffsNotes” version, giving the basics of our argument using excerpts copied directly from the paper. [Occasional comments from me–Jonathan Haidt–are interspersed in brackets] Please also see this post by Lee Jussim, explaining why we think this problem is so serious. In a later post Jarret Crawford summarizes the 33 commentaries on our article.

CITATION: Duarte, J. L., Crawford, J. T., Stern, C., Haidt, J., Jussim, L., & Tetlock, P. E. (2015). Political diversity will improve social psychological science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, 1-13.DOI:https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X14000430 [and try this link, with no paywall, or this link to the preprint version]

ABSTRACT

Psychologists have demonstrated the value of diversity – particularly diversity of viewpoints – for enhancing creativity, discovery, and problem solving. But one key type of viewpoint diversity is lacking in academic psychology in general and social psychology in particular: political diversity. This article reviews the available evidence and finds support for four claims: (1) Academic psychology once had considerable political diversity, but has lost nearly all of it in the last 50 years. (2) This lack of political diversity can undermine the validity of social psychological science via mechanisms such as the embedding of liberal values into research questions and methods, steering researchers away from important but politically unpalatable research topics, and producing conclusions that mischaracterize liberals and conservatives alike. (3) Increased political diversity would improve social psychological science by reducing the impact of bias mechanisms such as confirmation bias, and by empowering dissenting minorities to improve the quality of the majority’s thinking. (4) The underrepresentation of non-liberals in social psychology is most likely due to a combination of self-selection, hostile climate, and discrimination. We close with recommendations for increasing political diversity in social psychology.

1. Introduction

In the last few years, social psychology has faced a series of challenges to the validity of its research, including a few high-profile replication failures, a handful of fraud cases, and several articles on questionable research practices and inflated effect sizes… In this article, we suggest that one largely overlooked cause of failure is a lack of political diversity. We review evidence suggesting that political diversity and dissent would improve the reliability and validity of social psychological science…

We focus on conservatives as an underrepresented group because the data on the prevalence in psychology of different ideological groups is best for the liberal-conservative contrast – and the departure from the proportion of liberals and conservatives in the U.S. population is so dramatic. However, we argue that the field needs more non-liberals however they specifically self-identify (e.g., libertarian, moderate)…

The lack of political diversity is not a threat to the validity of specific studies in many and perhaps most areas of research in social psychology. The lack of diversity causes problems for the scientific process primarily in areas related to the political concerns of the Left – areas such as race, gender, stereotyping, environmentalism, power, and inequality – as well as in areas where conservatives themselves are studied, such as in moral and political psychology.

2. Psychology is less politically diverse than ever

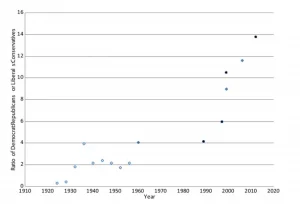

[In this section we review all available information on the political party identification of psychologists, as well as their liberal-conservative self descriptions. The graph below says it all. Whichever of those two measures you use, you find a big change after 1990. Before the 1990s, academic psychology only LEANED left. Liberals and Democrats outnumbered Conservatives and Republican by 4 to 1 or less. But as the “greatest generation” retired in the 1990s and was replaced by baby boomers, the ratio skyrocketed to something more like 12 to 1. In just 20 years. Few psychologists realize just how quickly or completely the field has become a political monoculture. This graph took us by surprise too.]

Figure 1. The political party and ideological sympathies of academic psychologists have shifted leftward over time. Circles show ratios of self-reports of liberal vs. conservative. Diamonds show ratios of self-reports of party preference or voting (Democrat vs. Republican). Data for 1924–60 is reported in McClintock et al. (1965). Open diamonds are participants’ recollections of whom they voted for; gray diamonds are self-reported party identification at time of the survey. Data for 1999 is reported in Rothman et al. (2005). Data from 2006 is reported in Gross and Simmons (2007). The right-most circle is from Inbar and Lammers (2012) and is the ratio of self-identified liberal/conservative social psychologists.

3. Three ways that the lack of diversity undermines social psychology

Might a shared moral-historical narrative [the “liberal progress” narrative described by sociologist Christian Smith] in a politically homogeneous field undermine the self-correction processes on which good science depends? We think so, and present three risk points— three ways in which political homogeneity can threaten the validity of social psychological science—and examples from the extant literature illustrating each point.

3.1. Risk point 1: Liberal values and assumptions can become embedded into theory and method

The embedding of values occurs when value statements or ideological claims are wrongly treated as objective truth, and observed deviation from that truth is treated as error.

[Example:] Son Hing, Bobocel, Zanna, and McBride (2007) found that: 1) people high in social dominance orientation (SDO) were more likely to make unethical decisions, 2) people high in right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) were more likely to go along with the unethical decisions of leaders, and 3) dyads with high SDO leaders and high RWA followers made more unethical decisions than dyads with alternative arrangements (e.g., low SDO—low RWA dyads).

Yet consider the decisions they defined as unethical: not formally taking a female colleague’s side in her sexual harassment complaint against her subordinate (given little information about the case), and a worker placing the well-being of his or her company above unspecified harms to the environment attributed to the company’s operations. Liberal values of feminism and environmentalism were embedded directly into the operationalization of ethics, even to the extent that participants were expected to endorse those values in vignettes that lacked the information one would need to make a considered judgment.

The appearance of certain words that imply pernicious motives (e.g., deny, legitimize, rationalize, justify, defend, trivialize) may be particularly indicative of research tainted by embedded values.

3.2. Risk point 2: Researchers may concentrate on topics that validate the liberal progress narrative and avoid topics that contest that narrative

Since the enlightenment, scientists have thought of themselves as spreading light and pushing back the darkness. The metaphor is apt, but in a politically homogeneous field, a larger-than-optimal number of scientists shine their flashlights on ideologically important regions of the terrain. Doing so leaves many areas unexplored. Even worse, some areas become walled off, and inquisitive researchers risk ostracism if they venture in.

[Example:] Stereotype accuracy. Since the 1930s, social psychologists have been proclaiming the inaccuracy of social stereotypes, despite lacking evidence of such inaccuracy. Evidence has seemed unnecessary because stereotypes have been, in effect, stereotyped as inherently nasty and inaccurate (see Jussim, 2012a for a review).

Some group stereotypes are indeed hopelessly crude and untestable. But some may rest on valid empiricism—and represent subjective estimates of population characteristics (e.g. the proportion of people who drop out of high school, are victims of crime, or endorse policies that support women at work, see Jussim, 2012a, Ryan, 2002 for reviews). In this context, it is not surprising that the rigorous empirical study of the accuracy of factual stereotypes was initiated by one of the very few self-avowed conservatives in social psychology—Clark McCauley (McCauley & Stitt, 1978). Since then, dozens of studies by independent researchers have yielded evidence that stereotype accuracy (of all sorts of stereotypes) is one of the most robust effects in all of social psychology (Jussim, 2012a). Here is a clear example of the value of political diversity: a conservative social psychologist asked a question nobody else thought (or dared) to ask, and found results that continue to make many social psychologists uncomfortable. McCauley’s willingness to put the assumption of stereotype inaccuracy to an empirical test led to the correction of one of social psychology’s most longstanding errors.

3.3. Risk point 3: Negative attitudes regarding conservatives can produce a psychological science that mischaracterizes their traits and attributes

A long-standing view in social-political psychology is that the right is more dogmatic and intolerant of ambiguity than the left, a view Tetlock (1983) dubbed the rigidity-of-the-right hypothesis…. But had social psychologists studied a broad enough range of situations to justify these broad conclusions? Recent evidence suggests not. The ideologically objectionable premise model (IOPM; Crawford, 2012) posits that people on the political left and right are equally likely to approach political judgments with their ideological blinders on. That said, they will only do so when the premise of a political judgment is ideologically acceptable. If it’s objectionable, any preferences for one group over another will be short-circuited, and biases won’t emerge. The IOPM thus allows for biases to emerge only among liberals, only among conservatives, or among both liberals and conservatives, depending on the situation. For example, reinterpreting Altemeyer’s mandatory school prayer results, Crawford (2012) argued that for people low in RWA who value individual freedom and autonomy, mandatory school prayer is objectionable; thus, the very nature of the judgment should shut off any biases in favor of one target over the other. However, for people high in RWA who value society-wide conformity to traditional morals and values, mandating school prayer is acceptable; this acceptable premise then allows for people high in RWA to express a bias in favor of Christian over Muslim school prayer. Crawford (2012, Study 1) replaced mandatory prayer with voluntary prayer, which would be acceptable to both people high andlow in RWA. In line with the IOPM, people high in RWA were still biased in favor of Christian over Muslim prayer, while people low in RWA now showed a bias in favor of Muslim over Christian voluntary prayer. Hypocrisy is therefore not necessarily a special province of the right.

These example illustrate the threats to truth-seeking that emerge when members of a politically homogenous intellectual community are motivated to cast their perceived outgroup (i.e., the ones who violate the liberal progressive narrative) in a negative light. If there were more social psychologists who were motivated to question the design and interpretation of studies biased towards liberal values during peer review, or if there were more researchers running their own studies using different methods, social psychologists could be more confident in the validity of their characterizations of conservatives (and liberals).

4. Why political diversity is likely to improve social psychological science

Diversity can be operationalized in many ways, including demographic diversity (e.g., ethnicity, race, and gender) and viewpoint diversity (e.g., variation in intellectual viewpoints or professional expertise). Research in organizational psychology suggest that: a) the benefits of viewpoint diversity are more consistent and pronounced than those of demographic diversity (Menz, 2012; Williams & O’Reilly, 1998); and b) the benefits of viewpoint diversity are most pronounced when organizations are pursuing open-ended exploratory goals (e.g., scientific discovery) as opposed to exploitative goals (e.g., applying well-established routines to well-defined problems; Cannella, Park & Hu, 2008). Viewpoint diversity may therefore be more valuable than demographic diversity if social psychology’s core goal is to produce broadly valid and generalizable conclusions. (Of course, demographic diversity can bring viewpoint diversity, but if it is viewpoint diversity that is wanted, then it may be more effective to pursue it directly.) It is the lack of political viewpoint diversity that makes social psychology vulnerable to the three risks described in the previous section. Political diversity is likely to have a variety of positive effects by reducing the impact of two familiar mechanisms that we explore below: confirmation bias and groupthink/majority consensus.

4.1. Confirmation bias

People tend to search for evidence that will confirm their existing beliefs while also ignoring or downplaying disconfirming evidence. This confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998) is widespread among both laypeople and scientists (Ioannidis, 2012). Confirmation bias can become even stronger when people confront questions that trigger moral emotions and concerns about group identity (Haidt, 2001; 2012). Further, group-polarization often exacerbates extremism in echo chambers (Lamm & Myers, 1978). [and note from the graph above that social psychology has become an echo chamber since the 1990s] Indeed, people are far better at identifying the flaws in other people’s evidence-gathering than in their own, especially if those other people have dissimilar beliefs (e.g., Mercier & Sperber, 2011; Sperber et al., 2010). Although such processes may be beneficial for communities whose goal is social cohesion (e.g., a religious or activist movement), they can be devastating for scientific communities by leading to widely-accepted claims that reflect the scientific community’s blind spots more than they reflect justified scientific conclusions (see, e.g., the three risk points discussed previously).

The most obvious cure for this problem is to increase the viewpoint diversity of the field. Nobody has found a way to eradicate confirmation bias in individuals (Lilienfeld et al., 2009), but we can diversify the field to the point where individual viewpoint biases begin to cancel each other out.

4.2. Minority influence

Minority influence research has focused on the processes by which minorities influence majority members’ (and thus the groups’) reasoning (e.g., Crano, 2012; Moscovici & Personnaz, 1980). Majorities influence decision-making by producing conformity pressure that creates cohesion and community, but they do little to enhance judgmental depth or quality (Crisp & Turner, 2011; Moscovici & Personnaz, 1980). They also risk creating the type of groupthink that has long been a target of criticism by social psychologists (e.g., Fiske, Harris, & Cuddy, 2004; Janis, 1972)…. There is even evidence that politically diverse teams produce more creative solutions than do politically homogeneous teams on problems such as “how can a person of average talent achieve fame” and how to find funding for a partially-built church ineligible for bank loans (Triandis, Hall, & Ewen, 1965)….

In sum, there are grounds for hypothesizing that increased political diversity would improve the quality of social psychological science because it would increase the degree of scientific dissent, especially, on such politicized issues as inequality versus equity, the psychological characteristics of liberals and conservatives, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Social psychologists have shown these effects in many settings; they could take advantage of them within their own ranks.

5. Why are there so few non-liberals in social psychology?

the evidence does not point to a single answer. To understand why conservatives are so vastly underrepresented in social psychology, we consider five explanations that have frequently been offered to account for a lack of diversity not just in social psychology, but in other contexts (e.g., the underrepresentation of women and ethnic minorities in STEM fields, e.g., Pinker, 2008).

5.1. Differences in ability

[Are conservatives simply less intelligent than liberals, and less able to obtain PhDs and faculty positions?] The evidence does not support this view… [published studies are mixed. Part of the complexity is that…] Social conservatism correlates with lower cognitive ability test scores, but economic conservatism correlates with higher scores (Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012; Kemmelmeier 2008). [Libertarians are the political group with the highest IQ, yet they are underrepresented in the social sciences other than economics]

5.2. The effects of education on political ideology

Many may view education as “enlightening” and believe that an enlightened view comports with liberal politics. There is little evidence that education causes students to become more liberal. Instead, several longitudinal studies following tens of thousands of college students for many years have concluded that political socialization in college occurs primarily as a function of one’s peers, not education per se (Astin, 1993; Dey, 1997).

5.3. Differences in interest

Might liberals simply find a career in social psychology (or the academy more broadly) more appealing? Yes, for several reasons. The Big-5 trait that correlates most strongly with political liberalism is openness to experience (r = .32 in Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloways’s 2003 meta-analysis), and people high in that trait are more likely to pursue careers that will let them indulge their curiosity and desire to learn, such as a career in the academy (McCrae, 1996). An academic career requires a Ph.D., and liberals enter (and graduate) college more interested in pursuing Ph.D.s than do conservatives (Woessner & Kelly-Woessner, 2009)…

Such intrinsic variations in interest may be amplified by a “birds of a feather” or “homophile” effect. “Similarity attracts” is one of the most well-established findings in social psychology (Byrne, 1969). As a field begins to lean a certain way, the field will likely become increasingly attractive to people suited to that leaning. Over time the group itself may become characterized by its group members. Professors and scientists may come to be seen as liberal just as nurses are typically thought of as being female. Once that happens, conservatives may disproportionately self-select out of joining the dissimilar group, based on a realistic perception that they “do not fit well.” [See Gross (2013)]…

Self-selection clearly plays a role. But it would be ironic if an epistemic community resonated to empirical arguments that appear to exonerate the community of prejudice—when that same community roundly rejects those same arguments when invoked by other institutions to explain the under-representation of women or ethnic minorities (e.g., in STEM disciplines or other elite professions). [Note: we agree that self-selection is a big part of the explanation. If there were no discrimination and no hostile climate, the field would still lean left, as it used to. But it would still have some diversity, and would work much better.]

5.4. Hostile climate

Might self-selection be amplified by an accurate perception among conservative students that they are not welcome in the social psychology community? Consider the narrative of conservatives that can be formed from some recent conclusions in social psychological research: compared to liberals, conservatives are less intelligent (Hodson & Busseri, 2012) and less cognitively complex (Jost et al., 2003). They are more rigid, dogmatic, and inflexible (Jost et al., 2003). Their lower IQ explains their racism and sexism (Deary, Batty, & Gale, 2008), and their endorsement of inequality explains why they are happier than liberals (Napier & Jost, 2008).

As conservative undergraduates encounter the research literature in their social psychology classes, might they recognize cues that the field regards them and their beliefs as defective? And what happens if they do attend graduate school and take part in conferences, classes, and social events in which almost everyone else is liberal? We ourselves have often heard jokes and disparaging comments made by social psychologists about conservatives, not just in informal settings but even from the podium at conferences and lectures. The few conservatives who have enrolled in graduate programs hear these comments too, and some of them wrote to Haidt in the months after his 2011 remarks at the SPSP convention to describe the hostility and ridicule that force them to stay “in the closet” about their political beliefs—or to leave the field entirely.

Haidt (2011) put excerpts from these emails online (in anonymous form); representative of them is this one from a former graduate student in a top 10 Ph.D. program:

I can’t begin to tell you how difficult it was for me in graduate school because I am not a liberal Democrat. As one example, following Bush’s defeat of Kerry, one of my professors would email me every time a soldier’s death in Iraq made the headlines; he would call me out, publicly blaming me for not supporting Kerry in the election. I was a reasonably successful graduate student, but the political ecology became too uncomfortable for me. Instead of seeking the professorship that I once worked toward, I am now leaving academia for a job in industry.

Evidence of hostile climate is not just anecdotal. Inbar and Lammers (2012) asked members of the SPSP discussion list: “Do you feel that there is a hostile climate towards your political beliefs in your field?” Of 17 conservatives, 14 (82%) responded “yes” (i.e., a response at or above the midpoint of the scale, where the midpoint was labeled “somewhat” and the top point “very much”), with half of those responding “very much.” In contrast, only 18 of 266 liberals (7%) responded “yes”, with only two of those responding “very much.” Interestingly, 18 of 25 moderates (72%) responded “yes,” with one responding “very much.” This surprising result suggests that the hostile climate may adversely affect not only conservatives, but anyone who is not liberal or whose values do not align with the liberal progress narrative.

5.5. Discrimination

The literature on political prejudice demonstrates that strongly identified partisans show little compunction about expressing their overt hostility toward the other side (e.g., Chambers et al., 2013; Crawford & Pilanski, 2013; Haidt, 2012). Partisans routinely believe that their hostility towards opposing groups is justified because of the threat posed to their values by dissimilar others (see Brandt et al., 2014, for a review). Social psychologists are unlikely to be immune to such psychological processes. Indeed, ample evidence using multiple methods demonstrates that social psychologists do in fact act in discriminatory ways toward non-liberal colleagues and their research.

[Here we review experimental field research: if you change a research proposal so that its hypotheses sound conservative, but you leave the methods the same, then the manuscript is deemed less publishable, and is less likely to get IRB approval]

Inbar and Lammers (2012) found that most social psychologists who responded to their survey were willing to explicitly state that they would discriminate against conservatives. Their survey posed the question: “If two job candidates (with equal qualifications) were to apply for an opening in your department, and you knew that one was politically quite conservative, do you think you would be inclined to vote for the more liberal one?” Of the 237 liberals, only 42 (18%) chose the lowest scale point, “not at all.” In other words, 82% admitted that they would be at least a little bit prejudiced against a conservative candidate, and 43% chose the midpoint (“somewhat”) or above. In contrast, the majority of moderates (67%) and conservatives (83%) chose the lowest scale point (“not at all”)….

Conservative graduate students and assistant professors are behaving rationally when they keep their political identities hidden, and when they avoid voicing the dissenting opinions that could be of such great benefit to the field. Moderate and libertarian students may be suffering the same fate.

6. Recommendations

[Please see the longer discussion of recommended steps on our “Solutions” page. In the BBS paper we offer a variety of specific recommendations for what can be done to ameliorate the problem. These are divided into three sections]

6.1. Organizational responses

[We looked at the list of policy steps that the American Psychological Association recommended for itself to improve diversity with regard to race, gender, and sexual orientation. Many of them work well for increasing political diversity, e.g.,:]

- Formulate and adopt an anti-discrimination policy resolution.

- Implement a “climate study” regarding members’ experiences, comfort/discomfort, and positive/negative attitudes/opinions/policies affecting or about members of politically diverse groups.

- Each organization should develop strategies to encourage and support research training programs and research conferences to attract, retain, and graduate conservative and other non-liberal doctoral students and early career professionals.

6.2. Professorial responses

There are many steps that social psychologists who are also college professors can take to encourage non-liberal students to join the field, or to “come out of the closet”: 1) Raise consciousness [acknowledge publicly that we have problem]; 2) Welcome feedback from non-liberals. 3) Expand diversity statements. [i.e., add “political diversity” to any list of kinds of diversity being encouraged].

6.3. Changes to research practices

- Be alert to double standards. 2. Support adversarial collaborations. [3. Improve research norms to increase the degree to which a research field becomes self-correcting.]

7. Conclusion

Others have sounded this alarm before (e.g., MacCoun, 1998; Redding, 2001; Tetlock, 1994)… No changes were made in response to the previous alarms, but we believe that this time may be different. Social psychologists are in deep and productive discussions about how to address multiple threats to the integrity of their research and publication process. This may be a golden opportunity for the field to take seriously the threats caused by political homogeneity.

We have focused on social (and personality) psychology, but the problems we describe occur in other areas of psychology (Redding, 2001), as well as in other social sciences (Gross, 2013; Redding, 2013). Fortunately, psychology is uniquely well-prepared to rise to the challenge. The five core values of APA include “continual pursuit of excellence; knowledge and its application based upon methods of science; outstanding service to its members and to society; social justice, diversity and inclusion; ethical action in all that we do.” (APA, 2009). If discrimination against non-liberals exists at even half the level described in section 4 of this paper, and if this discrimination damages the quality of some psychological research, then all five core values are being betrayed. Will psychologists tolerate and defend the status quo, or will psychology make the changes needed to realize its values and improve its science? Social psychology can and should lead the way.

Related Articles

Your generosity supports our non-partisan efforts to advance the principles of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement to improve higher education and academic research.