Education, Social Elites and Uneven Racial Progress

At the turn of the 20th Century, WEB Du Bois hoped a ‘Talented Tenth’ would eventually emerge from institutions of higher learning and leverage their social capital to lift up their peers. Putting social solidarity above their own interests, they would dedicate their efforts primarily to leading and empowering other people of color.

Today, Du Bois’ vision seems audacious due to the demands it ostensibly places upon elites of color: why should we be obligated to dedicate our efforts and hard-earned resources to rectifying inequality for others rather than placing this obligation upon whites? In Du Bois’ time, his vision was radical in part because postsecondary institutions were simply not open to black people.

For most of U.S. history, African Americans have been excluded from higher education (indeed, even primary education throughout most of the 19th century). To the extent that blacks were able to attend college at all, they were typically constrained to universities run by and for former slaves. Throughout Du Bois’ life (he died in 1963), the vast majority of higher education institutions in America would remain racially segregated.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) called for an end to segregation in public schools, which was interpreted to apply to public universities in principle. However, in practice, black students remained locked out for decades more.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 added new anti-discrimination protections for students of color. The 1965 Higher Education Act expanded funding for (and formally recognized) HBCUs, while expanding federal aid for students of lower incomes through Pell Grants and federal student loans – rendering college more financially accessible for people of humble backgrounds. Meanwhile, Executive Order 11246 (1965) empowered the federal government to enforce affirmative action – that is, to ensure that institutions were actively trying to recruit and integrate qualified applicants of color.

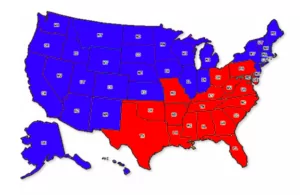

Nonetheless, 19 states continued to operate dual systems of higher education into the 1970s:

It was not until Adams v. Richardson (1973) that universities nationwide were finally compelled to admit qualified African American students – and it wasn’t until 1978 that the constitutionality of affirmative action and race-conscious admissions in higher ed was upheld by the Supreme Court (Regents of the University of California v. Bakke). Consequently, African Americans did not begin enrolling in universities in the U.S. in large numbers until the mid-1970s.

Atypical Exemplars

My father was born one year after Brown v. Board of Education, a ruling which ended segregation in principle, although not in practice. The same year as Adams v. Richardson, he enrolled in East Carolina University. Many of his peers who were able to go to college had enrolled in HBCU’s. Indeed, my father’s choice to enroll at East Carolina was controversial among some of his friends: why would he want to go to a ‘white school?’

And it was, essentially, a white school. At that time, less than 3% of the ECU student body was black (roughly 250 out of 10,000 students) – striking for a university based in a city (Greenville, NC) where more than a third of the population is African American.

However, as my father put it, he’d been attending all-black schools for virtually his entire life up to that point. He wanted to broaden his horizons, expand his opportunities, and break down walls. So he sought to enroll in a newly-integrating southern public university, despite the controversy it created among some of his peers.

Because East Carolina was eager to enroll more African Americans, they offered a generous aid package, allowing my father to attend despite his family’s lack of financial resources. However, after three years, he dropped out and joined the military.

This was not the end of my father’s story in higher education. He eventually returned to college, and even completed grad school. The combination of his exceptional military service and his educational credentials allowed him to achieve a degree of social mobility that he likely could not have imagined when he began his academic journey.

I didn’t grow up with my father (although today we are quite close). Nonetheless, I ended up following a similarly dramatic upward trajectory – in my case, making an improbable set of leaps from community college to the Ivy League. Stories like ours seem to abound these days, and for good reason. Among people of color who are the right combination of talented, shrewd, determined and lucky – and who are willing to pay the requisite costs – it is possible to make it far higher ‘up the ladder’ today than we ever could have in the past. However, in celebrating those who beat the odds, it can be easy to lose sight of the odds themselves (a phenomenon Bayesians describe as ‘base rate neglect’).

Yes, there has been immense change to the racial order over the course of my father’s lifetime. However, stories like his (and mine) remain far from typical. Most African Americans who are born poor stay poor. Meanwhile, most children of middle class and even wealthy black families are likely to experience downward mobility over their life course. Black families accumulate little wealth across generations.

African Americans continue to attend and (especially) graduate from college at much lower rates than their white peers – trends that are particularly pronounced among black men. Among those who attend, black students are overrepresented in less-prestigious schools and underrepresented at elite institutions. Black graduates typically leave college with far more debt than their white peers and tend to receive a significantly smaller socioeconomic return on their educational investments as compared to whites.

In short, beneath the encouraging changes over the course of my father’s lifetime lie troubling continuities.

Racial Reaganomics

In Undermining Racial Justice, historian Matthew Johnson explains that the arrival of large numbers of black college students like my father threatened to upend institutions of higher learning: their operations, their mission, their culture. However through ‘incorporating student dissent selectively into the institution’s policies, practices and values,’ college and university administrators were able to more-or-less ‘prevent activism from disrupting the institutional priorities that campus leaders deemed more important than racial justice.’ In a nutshell, ‘racial inclusion’ was made to be highly compatible with inequality.

Consider: racial activism resulted in the creation of Black Cultural Centers (BCCs) to help African American students cope with the alienation, isolation, hostility they often faced on campus at the time. Many universities established African American Studies programs. Many more changed the names of buildings and programs to pay tribute to prominent people of color. Diversity training is now an unavoidable part of campus life for faculty, staff and students.

And yet, African Americans remain significantly underrepresented in the professoriate, particularly in STEM fields – and they are significantly more likely to teach at public universities (as compared to elite private schools) and to be contingent faculty (rather than tenure or tenure-track). As a result of these trends, scholars of color have been particularly harmed by COVID-19 related austerity measures in higher ed.

That is, institutional inequalities have not only persisted but actually grown in recent years – even during the racial reckoning we are purportedly in the midst of. As unfortunate as this dynamic has been within institutions of higher learning, it is even worse in the broader society. Perhaps philosopher Olufemi Taiwo explained it best:

“One might think questions of justice ought to be primarily concerned with fixing disparities around health care, working conditions, and basic material and interpersonal security. Yet conversations about justice have come to be shaped by people who have ever more specific practical advice about fixing the distribution of attention and conversational power. Deference practices that serve attention-focused campaigns (e.g. we’ve read too many white men, let’s now read some people of colour) can fail on their own highly questionable terms: attention to spokespeople from marginalized groups could, for example, direct attention away from the need to change the social system that marginalizes them.

Elites from marginalized groups can benefit from this arrangement in ways that are compatible with social progress. But treating group elites’ interests as necessarily or even presumptively aligned with full group interests involves a political naiveté we cannot afford. Such treatment of elite interests functions as a racial Reaganomics: a strategy reliant on fantasies about the exchange rate between the attention economy and the material economy. Perhaps the lucky few who get jobs finding the most culturally authentic and cosmetically radical description of the continuing carnage are really winning one for the culture. Then, after we in the chattering class get the clout we deserve and secure the bag, its contents will eventually trickle down to the workers who clean up after our conferences, to slums of the Global South’s megacities, to its countryside. But probably not.”

The Social Justice Blind Spot

Enzo Rossi and Olufemi Taiwo recently explored how most formal barriers excluding women and minorities from the elite have been dismantled; this represents a real and significant change to the prevailing order. However, they argue, while it is important to recognize this progress as real (I would not be in my current position were it not for these reforms), it is also critical to recognize the benefits as quite limited, extending mostly to a small cadre of minority elites (and an even smaller number of elite aspirants).

Affirmative action, for instance, has primarily benefited people from the target groups who are already relatively well-off. That is, these measures have helped elites from historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups preserve or enhance their elite social position, but have not greatly expanded the share of minorities who can rise up the ladder (let alone reducing or altogether dismantling the hierarchies implied by the ‘ladder’ metaphor). Indeed, the percentage of African Americans who make it into the top income quintile is basically the same today as it was in 1960.

For the lucky few at the top, the elite discourse on race is often extremely helpful in our struggles to advance and consolidate our own position. For the white elites who continue to largely run the show, both elites of color and elite racial discourse are useful for legitimizing the institutions they control and justifying their own social position.

The result is something like a ‘conspiracy of silence’: all parties avoid acknowledging the realities that ‘the discourse’ and accompanying symbolic gestures towards antiracism

- Are radically out of step with the priorities and perspectives of most African Americans and other people of color, and

- Do precious little to mitigate racialized inequality ‘in the world.’

In so doing, all parties can avoid reckoning with even more uncomfortable realities about how, concretely, inequalities are reproduced and sustained – and by whom. As I’ve explained elsewhere:

“To understand how a social order is formed, reproduced and sustained, analysts should start by examining the upper quintile of society (the top 20%). This would include the millionaires and billionaires. However, it would also count the people who actually run the non-profits, government bureaucracies, corporations, universities and other institutions through which the ‘One Percent’ often attempt to exert their will; it would include those who shape public understanding of social reality as scholars, journalists, civic and religious leaders, teachers, artists, etc.

Critically, this ‘professional-managerial class’ does not passively receive, and mindlessly execute, the dictates of the ‘One Percent.’ Instead, we actively shape ‘the system’ in accordance with our own will and priorities. We facilitate the operation of the prevailing order, ensure its continued viability, and implement reforms. Put another way, we do not stand outside of society – nor are we passive observers of the racial order. We are active participants.

Of course, the tension is that the professional-managerial class in the U.S. skews liberal, especially on ‘cultural’ issues like race. We are the primary producers and consumers of antiracist, feminist and socialist content, and we staunchly resist understanding ourselves as ‘elites.’ However, we are also among the primary beneficiaries of systemic inequality. We are heavily invested in ‘the system’ and complicit in its operation. We often have trouble honestly reckoning with these latter facts as a result of the former. Consequently, we tend to blame others for societal injustice – especially our political or ideological opponents — while under-analyzing the (often larger) role that we, ourselves, play in producing and perpetuating unfortunate states of affairs. This is one reason problems persist despite widespread commitment to resolve them: everyone thinks someone else is responsible.”

Related Articles

Your generosity supports our non-partisan efforts to advance the principles of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement to improve higher education and academic research.