Why Conservatives and Liberals Are Not Experiencing the Same Pandemic

Although both groups live in the same country, conservatives and liberals in the U.S. do not seem to be experiencing the same COVID-19 pandemic. Liberals are very concerned about the disease; conservatives are comparatively apathetic.

This fact is puzzling because a long history of research in social psychology suggests that conservatives ought to be more worried than liberals about threatening diseases. Indeed, decades of research ties conservatism to threat sensitivity more broadly, and meta-analyses of dozens of studies reveal that conservatism is higher in societies with greater levels of disease threat.

So why on earth don’t conservatives seem especially threatened by a worldwide pandemic? In a set of three studies, my colleagues and I investigated this question. We considered two possibilities. First, might conservatives actually be less threatened by the current pandemic? After all, the pandemic has thus far tended to hit more liberal regions, like New York, harder than more conservative regions. It is therefore possible that conservative and liberal differences are driven by a divergence in actual experiences with COVID-19. Perhaps the roles would have been reversed if the original U.S. epicenter had been Houston instead of New York City.

Or, perhaps conservatives and liberals are viewing the pandemic through different ideological lenses – lenses that bias their perceptions of the pandemic’s potential threat. Decades of research indicate that people often see what they hope to see. It is possible, then, that liberals' and conservatives' political commitments have shaped their beliefs about the threat of COVID-19. For example, it could be that Trump's initial casual attitude toward the virus created a motivation among Republicans to downplay the severity of the threat, or created a motivation among Democrats to amplify the seriousness of the threat. Thus, the ideological match between pre-existing political goals and perceptions of the pandemic's effects on those goals, rather than differences in actual experiences and observations of the consequences of the virus, may explain the apparent disagreement about its severity.

To investigate, we created and factor analyzed measurements of how threatening people perceived COVID-19 to be, desired political outcomes related to COVID-19 (such as the degree to which they wanted the government to enforce social distancing), and the extent to which they had been affected by COVID-19. Participants also completed standard measurements of political ideology. Using modern mediational analyses, we examined whether the relationship between political ideology and perceived COVID-19 threat was better explained by participants’ political lens (how their pre-existing political beliefs interfaced with COVID-19) than by their actual experiences (how they have been affected directly by COVID-19).

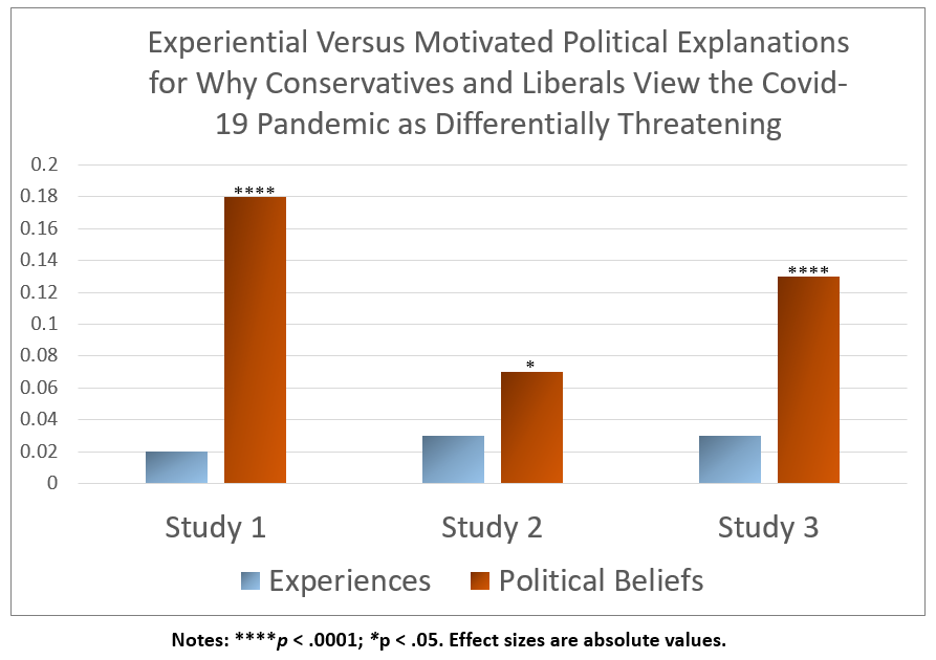

The results were striking. We found little evidence that different experiences with COVID-19 account for liberals’ and conservatives’ different views of the pandemic. Instead, participants’ desired political outcomes more consistently accounted for ideological differences in disease threat perception. The figure below reports the indirect effects for both political beliefs and experiences across our three studies. These indirect effects are measurements of the degree to which the relationship between political ideology and perceived COVID-19 threat is accounted for by (a) desired political outcomes related to COVID-19 or (b) participants' exposure to or experiences with the effects of the disease. As clearly indicated, it is participants’ political desires – and not their level of experience or exposure – that account for the different threats liberals and conservatives assign to COVID-19.

What kinds of ideological goals were most important in explaining conservatives’ relative apathy toward COVID-19? Out of six, the strongest effects emerged for goals that involved government-imposed social distancing rules. Conservatives oppose the government telling them when they can or cannot leave their homes; liberals support such policies. Because a threatening disease might validate government interventions that conservatives dislike, conservatives appear motivated to downplay the severity. Or conversely, because a threatening disease might validate government interventions that liberals do like, liberals seem motivated to magnify the threat. Note that our results cannot say which of these is happening in greater measure.

Thus, it is these ideological lenses – and not direct experiences – that appear to explain better liberals’ and conservatives’ different views of the pandemic. In a sense, the proverbial cart may be driving the proverbial horse: rather than the actual threat of the disease influencing political policy preferences, political policy preferences are influencing perceptions of disease threat.

Our findings suggest that this pandemic might drive an already-divided nation even further apart. However, our results also offer a path by which the pandemic could ultimately bring ideological groups closer together. We found that the general effect of ideology on perceived COVID-19 threat significantly decreased at higher levels of experience with COVID-19. Conservatives view the disease as less threatening than liberals, but this difference shrinks among participants who have been more impacted by the disease. Thus, although a lack of experience did not account for conservatives’ lower threat perceptions, the more experience they had, the less their own ideological goals mattered. As the effects of the disease grow, then, ideological groups’ attitudes toward the disease may start to merge.

Related Articles

Your generosity supports our non-partisan efforts to advance the principles of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement to improve higher education and academic research.