Opportunity Lost: What Happens When Students Can’t Study Abroad

As COVID-19 continues to generate uncertainty about the short-term future of higher education, one thing that is certain is that college students likely won’t be studying abroad anytime soon. As of March 19 and until further notice, the U.S. State Department issued a Global Health Level 4 Travel Advisory that U.S. citizens should avoid international travel.

Studying abroad is touted as one of the high-impact practices that students can experience in college. According to The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE), high-impact practices share several traits: They require significant time and effort, typically occur outside the classroom, facilitate meaningful exchanges as well as collaboration with diverse faculty and students, and provide rich and consistent feedback.

In 2016-2017, over 330,000 college students in America studied abroad for credit, a 40,000 increase from five years prior. The Institute of International Education estimates that about 10.9% of all undergraduate students, and as high as 16% of degree-earners, study abroad at some point during college. This means that somewhere in the realm of half a million college students in the United States per year will leave college and enter a diverse workforce after a life-changing experience studying abroad.

The benefits of studying abroad are well-documented through student survey data and personal stories of transformation. What happens if Covid-19 steals these opportunities from students?

Our research teams at The Ohio State University, North Carolina State University, and Interfaith Youth Core surveyed thousands of students at over 120 colleges and universities across their four years in college (2015-19) to discover how experiences like studying abroad affect their beliefs and behaviors. Our study, IDEALS, ultimately sought to uncover how prepared students are to engage constructively in a society of diverse religious and nonreligious beliefs.

At college entry and college exit, we asked students about their “global citizenship,” or their level of agreement with a series of statements (e.g. strongly agree, somewhat agree, and so on) including:

- I am actively working to foster justice in the world.

- I frequently think about the global problems of our time and how I will contribute to resolving them.

- I am currently taking steps to improve the lives of people around the world.

- I am actively learning about people across the globe who have different religious and cultural ways of life than I do.

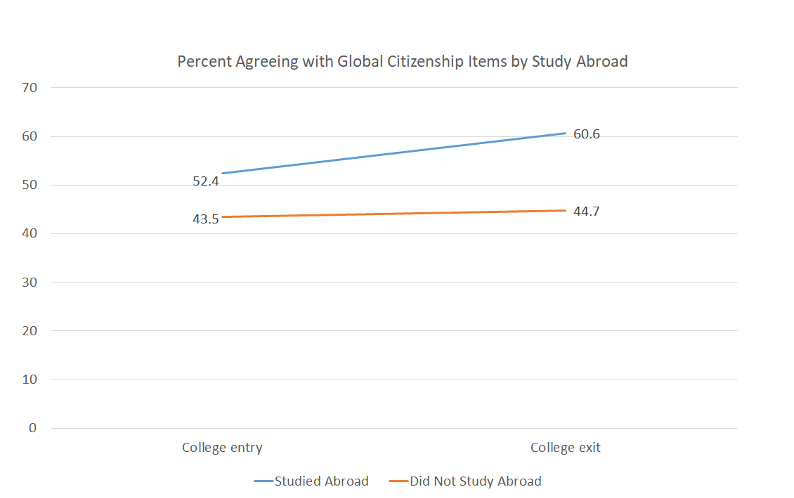

We discovered that for students who studied abroad in college, a greater proportion of them agreed with these statements by the time they left college (60.6%) than when they started college (52.4%), with a growth of 8 percentage points. This growth trend held true regardless of students’ gender, race/ethnicity, religious/nonreligious beliefs, or political affiliation.

Among students who did not study abroad while in college, the proportion who agreed with these statements at the end of college (44.7%) remained about the same as when they began (43.5%), with a growth of only 1 percentage point.

By the end of four years in college, IDEALS found a 16% gap between students who studied abroad (60.6%) and those who did not (44.7%), when looking at their level of agreement with our global citizenship items. This means that students who did not study abroad during college were significantly less likely to report that they are reflecting on the global problems of our time, actively working to foster justice in the world, seeking justice and working to improve the lives of others, and actively learning about those they have differences with.

Without opportunities to study abroad, America’s colleges and universities will graduate a smaller proportion of students who possess the qualities that our fractured and hurting society desperately needs right now. These graduates might be just as innovative, but less committed to using their savviness to solve humanity’s problems or serve the common good. A smaller number may leave college aware of or spirited about global conflicts and injustices. Fewer college graduates will know how to apply their expertise to address violence, disease, and political persecution, or even care to.

Could colleges create alternative experiences that attempt to salvage the benefits of studying abroad? Potentially. Administrators have done this before, for example, after 9/11 and the outbreak of SARS. But according to Brian Whalen, CEO of the Forum on Education Abroad, “The current [COVID-19] crisis is different and will leave lasting changes to the way that institutions think about and practice education abroad...Institutions are very likely to be wary of restarting education abroad in the way that it has been practiced up to now.”

An alternative is that institutions no longer define education abroad as strictly crossing national borders. Rather, Whalen recommends that we “conceive of [studying abroad] as an educational framework that promotes the mobility of students’ minds -- Minds engaged in confronting other cultures and worldviews that help overcome their biases.” In other words, studying abroad should become more of an educational model than a destination on a map.

Reconceptions of studying abroad will be critical if the post-COVID college still hopes to produce globally-educated citizens who understand the interconnectedness of our world, resist xenophobia, and strive to alleviate world problems in ethically and environmentally responsible ways.

As our research with IDEALS has shown, these globally conscious learning opportunities show great promise to produce the college graduates that America can be proud of.

Related Articles

Your generosity supports our non-partisan efforts to advance the principles of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement to improve higher education and academic research.