White Privilege Rhetoric: Shifting Views but Losing Voters

While the last decade of American politics has left many pessimistic, it has proved fascinating for the field of political psychology. American politics and public opinion are in flux, and two particular trends stand out: (1) increasing polarization, and (2) the rapid move to the left on social issues among white Democrats, a trend popularized as “The Great Awokening”. From these two findings, and the election of President Trump, one might get the misleading impression that Republicans and conservatives are moving to the right on the same issues. However, their attitudes have stayed mostly constant, and if anything moved slightly to the left, with more Republicans today supporting gay marriage and saying that the country needs to make more changes to address racism than in the recent past.

Thus, the public has reacted to the left’s campaign for racial and gender equality in somewhat paradoxical ways. Liberals have succeeded in shifting public opinion in their direction. Still, the Democratic Party’s immediate prospects seem little better than they have been in years past, despite demographic trends moving in its direction. Gains made from the increasing non-white share of the population have often balanced out—and in 2016 were overwhelmed—by losses among whites, particularly in the swing states that decided the election. The public is increasingly concerned with social justice issues, yet the percentage of the public identifying with the Democratic party has remained stagnant over the last decade.

Co-authored by me, George Hawley, and Eric Kaufmann, a new paper titled “Losing Elections, Winning the Debate: Progressive Racial Rhetoric and White Backlash,” seeks to understand trends in American politics in the era of a more liberal public and continuing polarization. We recruited a representative sample of white Americans for a preregistered survey. Respondents received a text about former candidate for president Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, a white woman whose short-lived run was notable for its embrace of the rhetoric of white privilege. Using randomized treatments, we first led respondents to believe that Gillibrand was either moderate or left-wing on issues of income redistribution. In the second treatment, it was said that she either favored reparations for African Americans and affirmative action or promised to help all Americans. Finally, we provided some participants with a real quote from Gillibrand that put forth a unifying message, while the rest received a quote from her promising to address white privilege.

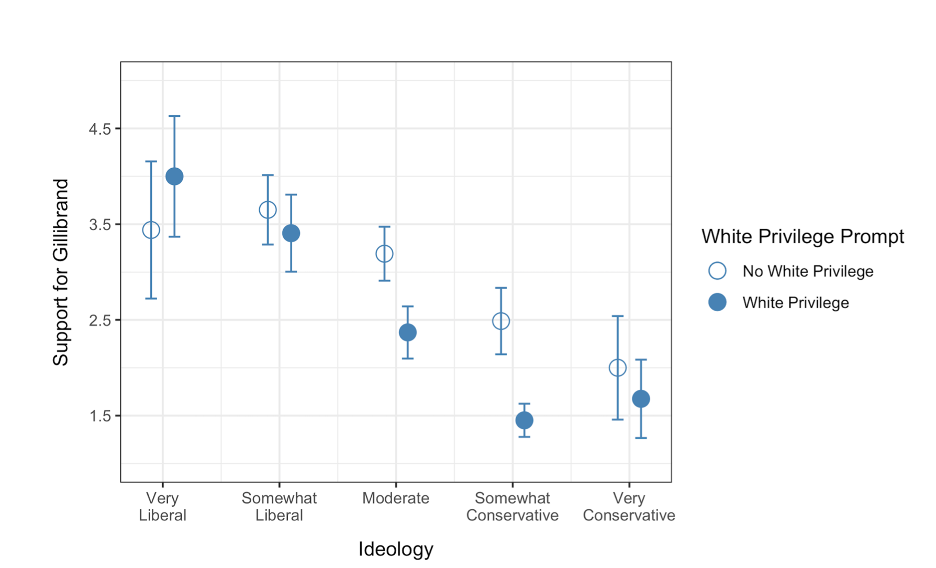

We found significant backlash among white Americans in their reports of whether they would vote for Gillibrand or be worried were she to become president. While 36% reported that they would vote for Gillibrand in the control condition, a third of her support was lost in the white privilege condition, down to 24%. Having a respondent read the passage about white privilege was the equivalent of a one-point shift on a five-point measure of ideology, that is going from somewhat liberal to moderate, or from moderate to somewhat conservative. Arguing for reparations and affirmative action also reduced support, albeit to a lesser extent. Figure 1 shows change in support for Gillibrand based on ideology and whether respondents received the white privilege treatment.

Figure 1. Effect of discussion of white privilege on support for Gillibrand, with 95% confidence intervals, p < .001 across entire sample.

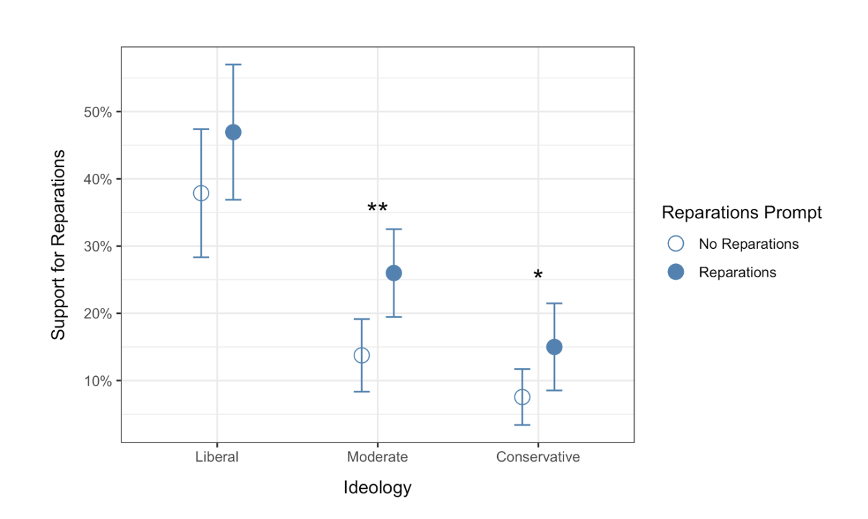

Despite these findings, however, there was no broader backlash in terms of actual attitude change. We had hypothesized that hearing about white privilege might increase white identity, but in fact observed weak evidence for the opposite effect among conservatives. Support for affirmative action remained unchanged across all treatments. Finally, support for reparations increased when Gillibrand advocated for such policies, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Dichotomous support for reparations based on ideology and prompt showing Gillibrand supporting reparations. Note: p < .05*, p < .01**

Thus, in the aggregate, our results suggest that a Democratic politician might lose votes from taking left-wing positions on race, but still move public opinion to the left on these issues. This might explain how, as the party becomes more focused on identity issues, Democrats can win the battle for public opinion but lose elections. For reasons explained in the paper, we do not believe the shift in favor of reparations was caused by social desirability bias or participants misrepresenting their views.

In 1975, political commentator and future presidential candidate Pat Buchanan wrote a book called Conservative Votes, Liberal Victories. Since that time, Republicans have been in power in Washington more often than not. Yet on issues related to race, gender, and sexual orientation, their policy victories have been few and far between, and shifts in public opinion may make successes on these fronts even less likely in the future. Our research presents one possible reason why. By taking left-wing positions on race, Democrats may suffer consequences at the ballot box but help move the American public further left. Future research should more fully explore this possibility and investigate whether there are analogous paradoxical effects with regards to non-racial issues—and whether conservatives might similarly have the option of sacrificing short-term political success for long-term societal change.

Related Articles

Your generosity supports our non-partisan efforts to advance the principles of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement to improve higher education and academic research.